Introduction

A great deal of research has been done in recent decades to identify the most effective teaching methods. Some of the results have been exactly what experienced teachers might expect, while others have been more surprising.

Axiom Science courses reflect the principles uncovered by this work, with the goal of equipping you to provide the best possible learning opportunities for your children. Here are three important principles that characterize the most effective approaches to teaching.

Principle 1: Long-term study beats cramming

In a landmark paper published in Psychological Science, Nicholas Cepeda and his colleagues examined the effects of different study schedules on a total of 1350 participants.1 They finally proved what many teachers and students have known (or at least suspected) for a long time: Cramming immediately before a test may improve test scores, but the material learned is quickly forgotten. By contrast, if you really want to develop and retain understanding of a subject in the long term, it’s necessary to study and review the material repeatedly over an extended period of time.

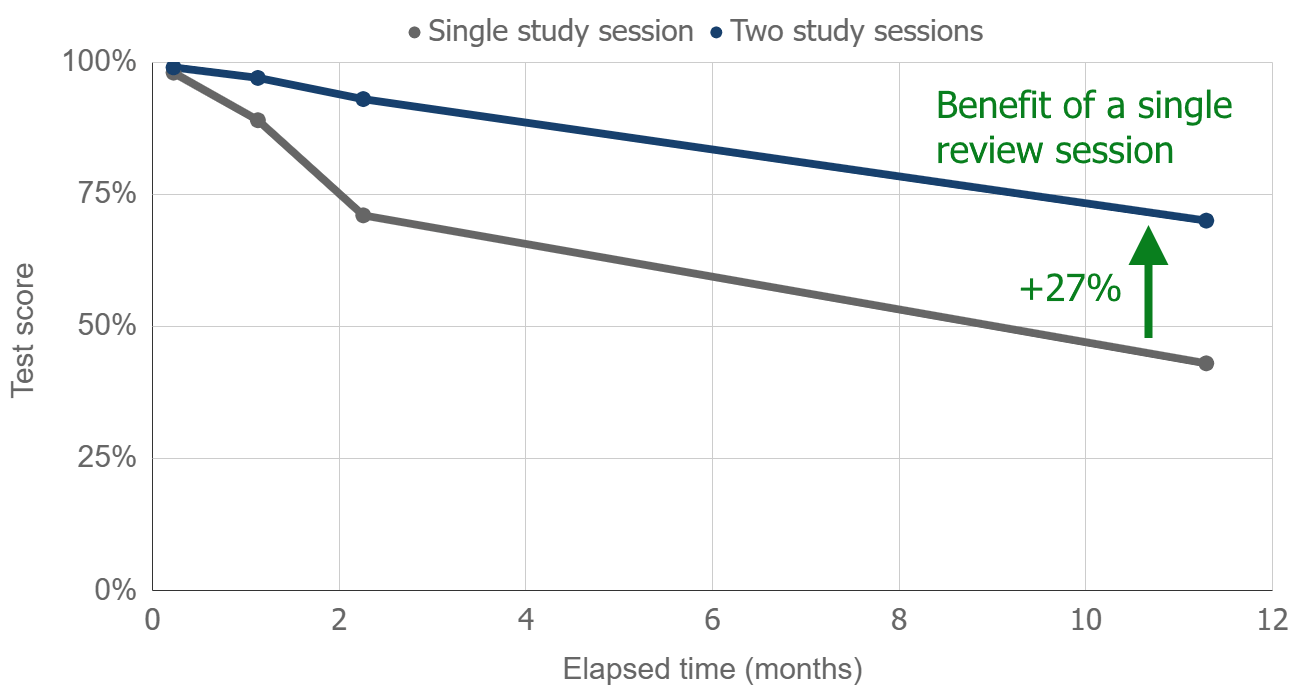

Imagine two groups of students. The first group receives all their teaching in a single session, while the second group receives the same amount of teaching divided into two sessions spaced a few days or weeks apart. Members of each group are then tested at intervals to determine how much they will be able to remember after the teaching is finished. The key question is this: How much knowledge will each group be able as the months go by?

The gray line shows what happens to test scores if all the teaching is squeezed into a single session. This simulates the effect of cramming. By contrast, the blue line shows the results of dividing the same amount of teaching into two separate sessions. Predictably, both groups score nearly 100% initially, the scores in both groups decline over time. But the scores in the single session group decline much more rapidly, dropping to 43% after almost a year, while the students who received two separate study sessions retained 70% of what they had learned.

The effects of a single review session on knowledge retention over time

Source: Cepeda et. al. (2008)

That’s a 27% improvement in test scores — quite a bonus for your students! And remember: that comes from just a single review session, with no overall increase in study time. Adding extra reviews during the year would obviously improve performance even more. Indeed, Cepeda and his colleagues explain that in some circumstances a single review session can double the amount of material remembered.

These results have profound implications for course design. Traditionally, many courses work through individual topics one by one, perhaps testing as they go, but once a topic has been covered, the students never return to it again. This is a highly inefficient way of teaching. The earlier material gradually fades from memory, and by the end of the course the students have forgotten most of what they learned at the beginning. If there is a final test, students who spend a few days frantically cramming are likely to get a better score. But none of them will be able to remember much in the long term.

You can probably identify personally with this experience. How much can you really remember about what you studied at school?

You can probably identify personally with this experience. How much can you really remember about what you studied at school? You can probably recall some of what your learned, but only in subjects that really captured your imagination, or which you later studied at a higher level, or which you returned to in your professional life. Those topics continued to percolate through your mind, week by week, month by month, and year by year, with the result that you can still recall them vividly decades later. By contrast, in other subjects, you may have passed the test, but they’re now long forgotten.

Yes, this is great! I get this!

This approach to learning is much more rewarding for the students themselves. Of course, some students may feel uncertain when they encounter new ideas for the first time. But as they progress through the course, they return again and again to those same topics from different angles, and gradually everything starts to make sense. Over time, students start to get that tremendously rewarding feeling, “Yes, this is great! I get this!”

Principle 2: Well-designed tests improve retention

No one really likes tests, and of course we all recognize that it’s possible to have too many of them. Children don’t grow taller simply by being measured every day; in the same way, just testing and retesting over and over again doesn’t help children learn. Too much testing can be discouraging and stressful, and reduces the time available for actual teaching.

In an authoritative 2006 article entitled “The Power of Testing Memory,” psychologists Henry Roediger and Jeffrey Karpicke describe what they call “the testing effect” — namely, the “surprising phenomenon” whereby “tests enhance later retention more than additional study of the material.”2

Their extensive review includes not just laboratory-based studies, but also the application of the results to real-life educational settings. Their conclusion is clear: “Frequent testing in the classroom may boost educational achievement at all levels of education.”

Testing does have a place in a well-designed teaching process

Other studies explain the mechanism behind the testing effect. The bottom line is simple: the very act of retrieving an idea from memory during a test or other assessment is what psychologists call a learning event — that is, a cognitive process that produces a lasting change in knowledge or understanding. The impact of such a first-hand learning event is much more profound and long-lasting than merely hearing an explanation from someone else.

If you’re a teacher, you’ve almost certainly experienced something like this yourself. Perhaps you encountered an idea that’s new and intriguing to you, and you thought to yourself, “I should definitely include that in my teaching sometime.” At the time, it seems clear in your mind — you’re sure you understand it. But later, when you’re preparing to share it with your students, you get into a bit of a tangle. You realize that you didn’t understand the new idea quite as well as you had imagined. You’re forced to think hard, perhaps to re-read the material again, and only then does it become clear enough in your mind that you can explain it well to your class.

That’s the testing effect in action. The original encounter was your “lesson,” and the lesson preparation was your “test”. That lesson prep was a highly effective learning event for you — just like a test, it forced you to recall more clearly what you thought you already understood. Initially, you discovered to your surprise that you didn’t understand it as well as you thought you did! Wonderfully, your lesson prep also had the effect of crystallizing the idea in your mind, so that when you taught it to your students, it was clear and exciting for them.

Axiom Science courses are designed to take advantage of the testing effect... to get beyond superficial familiarity and achieve true mastery of the subject

Axiom Science courses are designed to take advantage of the testing effect. Our courses include 50 quizzes, spaced out among almost 200 video lessons and reviews, along with 20 hands-on labs, with the aim of enabling students to get beyond superficial familiarity and achieve true mastery of the subject. When your students hear “Quiz,” encourage them to think, “This is my opportunity to really get to grips with what I’ve learned!”

Principle 3: Desirable difficulties produce the best results

Of course, not all difficulties are desirable. Badly designed teaching can be difficult in ways that are profoundly unhelpful. Muddled explanations or disorganized ideas just create confusion, and too many new ideas introduced too quickly leave students overwhelmed. If teachers fail to integrate new themes into existing material, or don’t include regular reviews, students will be unable to connect the various topics into a coherent whole, and everything will quickly be forgotten. If clear feedback is not provided, mistakes will become ingrained. Distracting or irrelevant material increases cognitive demand without focusing the students’ minds on what’s important. All of these pedagogical mistakes create undesirable difficulties — they make lessons more difficult without helping students learn, and many students will become discouraged and give up.

Not all difficulties are desirable... pedagogical mistakes create undesireable difficulties — they make lessons more difficult without helping students learn

But desirable difficulties are very different. The most effective teaching introduces new ideas in a way that is intriguing and challenging, yet manageable. It makes frequent connections to themes introduced previously, so that students gradually build up a coherent picture of the whole subject. The quizzes discussed above form part of this picture, prompting students to recall previous material in different contexts, and providing clear feedback so that even mistakes become valuable learning events. And science courses in particular offer unique opportunities to increase students’ motivation by making frequent connections to real-world practical applications of scientific principles.

The best academic learning is like good physical training... great teaching challenges students with the thrill of discovering things about which they never even dreamed

The best academic learning is like good physical training. Athletes need ongoing exposure to new challenges that push their limits without overloading them or causing injury. It’s obviously foolish to put hundreds of pounds on the shoulders of a rookie linebacker in the gym, or to send a new runner out to run fifty miles in their first week. But gradually increasing the weight or the mileage over an extended period of time is exactly what athletes need. The process will be exhausting at times, but the results of a well-designed training program will leave athletes fitter, faster, and stronger than they ever believed possible.

You can see why this third principle is ultimately the most encouraging. The experience of being challenged academically is the experience of growing in understanding of the world. This is our goal at Axiom Science — to lead students towards a deep and lasting understanding of the physical world, as every day they uncover more and more reasons to give glory to God, the Creator of all things.

Notes

1 Cepeda, Nicholas J., Edward Vul, Doug Rohrer, John T. Wixted, and Harold Pashler. “Spacing Effects in Learning: A Temporal Ridgeline of Optimal Retention.” Psychological Science, vol. 19, no. 11, 2008, pp. 1095-1102. Retrieved from https://laplab.ucsd.edu/articles/Cepeda%20et%20al%202008_psychsci.pdf

2 Roediger, Henry L. III, and Jeffrey D. Karpicke. “The Power of Testing Memory: Basic Research and Implications for Educational Practice.” Perspectives on Psychological Science, vol. 1, no. 3, 2006, pp. 181-210. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237268918_The_Power_of_Testing_Memory_Basic_Research_and_Implications_for_Educational_Practice